As the US wanes, China gains | The Australian

AUGUST 05, 2010

By CAMERON STEWART, ASSOCIATE EDITOR

BENEATH the radar, almost by stealth, the tectonic plates of power are shifting in the Pacific Ocean. A resurgent China is baring its teeth at the once indomitable US Pacific fleet. The certainty of US hegemony over this vast ocean, which Australians have taken for granted since World War II, is being challenged.

BENEATH the radar, almost by stealth, the tectonic plates of power are shifting in the Pacific Ocean. A resurgent China is baring its teeth at the once indomitable US Pacific fleet. The certainty of US hegemony over this vast ocean, which Australians have taken for granted since World War II, is being challenged.

But this steady transformation of our security outlook has failed to capture public attention in Australia precisely because it has been so steady and does not lend itself to an easy headline in a world of 24-hour news cycles.

It is being driven by twin factors: the rise of China as a Pacific power and the decline of imperial America.

The first is undeniable. China is working feverishly to create a navy and a land-based anti-ship missile system that will prevent the US 7th Fleet from dominating its territorial waters, including Taiwan.

The second assumption is more contentious. But there is a growing view among some of the world’s foremost thinkers that the American empire is now in inexorable decline and that the sun will soon set on the US era of hegemony in the Asia-Pacific.

This Pacific retreat, they argue, will not be voluntary but will be forced on Washington by financial pressures as the world superpower teeters under the burden of its $US1.47 trillion deficit, now equal to 10 per cent of GDP.

Last week, Harvard economist Niall Ferguson delivered a stark warning about the imperial decline that affects great powers when they are no longer able to manage their economies.

Giving the John Bonython Lecture at the Centre for Independent Studies in Sydney, Ferguson warned that the US economy is now so mired in debt that Washington has little choice but to try to save itself by slashing defence spending.

„The US is on a completely unsustainable fiscal course with no apparent political means of self-correcting,“ he said.

„Military expenditure is the item most likely to be squeezed to compensate because, unlike mandatory entitlements [such as social security], defence spending is discretionary.“

He points out that the US Congressional Budget Office’s latest projections say debt could rise above 90 per cent of GDP by 2020 and to an astonishing 344 per cent by 2050 — a figure that would see net interest payments become a crippling 85 per cent of revenue.

„What if the sudden waning in American power that I fear brings to an abrupt end the era of hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region? Are we ready for such a dramatic change in the global balance of power?“ he asks

While Ferguson’s warnings will be dismissed by some as alarmist, there is an underlying logic to many of his arguments.

For the first time since the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001, there is serious debate in the US about the size and cost of the armed forces.

A decade of rapid increases in military spending have spluttered to a halt, and with US combat forces withdrawing from Iraq and due to leave Afghanistan from 2014, the mood is ripe for cuts in military spending.

„We’re going to have to take a hard look at defence if we are going to be serious about deficit reduction,“ Erskine Bowles, co-chairman of the US Congress’s deficit-reduction commission, said last month.

Even Defence Secretary Robert Gates admits „the gusher [on military spending] has been turned off and will stay off for a good period of time“.

According to a report last month by Washington’s Centre for Strategic and International Studies, the legacy of the global financial crisis will be to stymie US defence spending in the long term relative to nations such as China, Russia and India.

„The 2008 financial crisis had a more detrimental impact on advanced economies like the US than on developing economies like China and India,“ according to the report.

It says China and Russia have increased defence spending at a faster rate than the US in the past decade and that this will continue because they have had a more robust economic recovery.

„Revenues will decrease for the US government as debt and entitlements will exponentially grow,“ it says. „Defence spending is set to decrease in real terms over the long term. As such, the Pentagon will have to grapple with dwindling resources [and] this may be a serious challenge.“

One of Australia’s leading defence analysts, Mark Thomson, agrees.

„The GFC has left US public finances in a parlous state,“ he says in a recent report for the Australian Strategic and Policy Institute.

„It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the scene is set for a large downward swing in US defence spending like those which occurred in 1953, 1970 and 1984.

„In the absence of a clear and present strategic imperative, the next decade will once again see a contraction of US military power — a contraction that is likely to accelerate in the decades that follow, given the long-term fiscal outlook.“

The good news for Australia is that even if US military spending declines and the Pacific fleet dwindles in size and potency, it will be many years before it is seriously challenged as the pre-eminent power in the region.

The US will this year spend more than $US700 billion on national defence, more than the next 34 highest spending countries in the world combined.

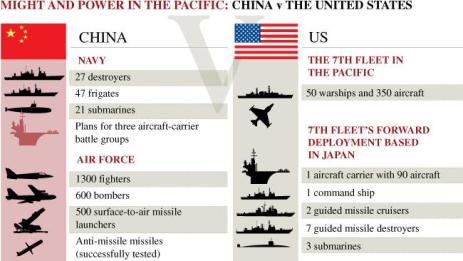

The US 7th fleet in the western Pacific has more than 50 warships, 350 aircraft and 60,000 marines at its disposal, including 18 permanently forward-deployed warships operating from Japan and Guam.

The fleet holds a clear military superiority over Chinese naval forces today and is likely to do so for years to come, even allowing for a steady decline in US defence spending that will eventually affect its military presence in the region.

But what troubles some Americans is that China’s naval build-up poses a more immediate risk to US naval operations close to the Chinese coast, raising doubts about the ability of US forces to defend Taiwan.

As the chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, said last month, China is making a fundamental „strategic shift, where they are moving from a focus on their ground forces to focus on their navy, and their maritime forces and their air force“.

China is pumping many billions of dollars into new warships and submarines with the aim of denying the US Navy the ability to rule supreme in East Asian waters.

It has also displayed a willingness to scrap with US forces in the region, including the harassment and obstruction of the US naval survey ship Impeccable by five Chinese vessels and a maritime aircraft in the South China Sea in March last year.

Several months later a Chinese submarine hit an underwater sonar array being towed by the destroyer USS John McCain near Subic Bay in The Philippines.

„China’s military ambitions and behaviour, even though focused relatively close at home, indicate nothing less than a bid for geopolitical pre-eminence in East Asia,“ says maritime security expert Chris Rahman in a recent ASPI report on China’s maritime agenda.

„Some have argued that an essentially stable geostrategic balance exists in East Asia, with China dominant on land and the US dominant at sea. „However, that argument misunderstands the challenge that China’s seaward expansion poses to the US system of regional security.

„It is the [People’s Liberation Army’s] growing ability to deny access to East Asian seas in a crisis or conflict, and so to disrupt the security system led by US Pacific command, that most threatens regional order and harmony at sea.“

One of the US’s leading strategic thinkers, John Mearsheimer from the University of Chicago, said in Australia this week that China will seek to push the US out of Asia.

„I think that China cannot rise peacefully and that this is largely predetermined,“ he says.

Of greatest concern for the US and the West is the development by China of an anti-ship missile with a range of nearly 900 miles (1450km), specifically designed to defeat US carrier strike groups.

Gates has said bluntly China’s „investments in anti-ship weapons and ballistic missiles could threaten America’s primary way to project power and help allies in the Pacific, particularly our forward bases and strike carrier groups“.

China’s ambitions in the Pacific are, at present, limited to denying US forces the ability to operate from forward bases such as Okinawa and Guam, as well as sowing doubts in the minds of Americans about the safety of US carrier groups close to the Chinese mainland.

Some believe the US military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan have come at the cost of other defence programs that would have been relevant to the Chinese threat, such as the decision to cancel the F-22 fighter program — a plane that was considered uniquely capable of penetrating China’s increasingly sophisticated air defence systems.

The Obama administration is taking China’s naval build-up in the region seriously and has recently moved to shore up its alliances in East Asia.

The US last month announced it would resume relations with Indonesia’s controversial special forces, Kopassus, in what The Washington Post described as „the most significant move yet by the United States to strengthen ties in East Asia as a hedge against China’s rise.“

The Obama administration has also taken recent steps to strengthen its ties with traditional allies such as South Korea and Japan, as well as Malaysia.

Alan Dupont, director of the Centre for International Security Studies at the University of Sydney, says America’s overtures have been received well in a region that is also nervously eyeing China’s naval expansion.

„In effect, China now faces the prospect of a revitalised and extended US alliance structure in Asia, which includes a second tier of de facto Asian partners, which worries about China’s rise as much as the US,“ Dupont says.

„A problem with this strategy is that the US is not dealing from a position of strength. Suffering from imperial overstretch and unprecedented peacetime fiscal deficits, which threaten to erode US military capabilities and foreign policy clout, this hardly seems the time for Asian states to put their faith in Uncle Sam.“

For a country such as Australia, which would rely heavily on the US Pacific fleet to protect it against a belligerent China, the prophecies of experts such as Ferguson are disturbing. Ferguson claims Australians have not thought about such big-picture trends as the possible decline of the US in the Pacific.

Regional security has not been discussed by either Prime Minister Julia Gillard or Opposition Leader Tony Abbott in this election campaign.

But if these prophecies come true and American power in the Pacific begins to wane, Australia will be unable to ignore the grave implications for its security.

Hat dies auf "Globalisierung zaehmen" rebloggt.